The Age of Biography

Did you know that in Elizabethan England, most people had sex fully clothed because the Renaissance naked body was so grubby and smelly? Or that Shakespeare’s plays contain in total 1300 sexual allusions, and no less than 66 terms for a vagina? Some of my favourite examples of the latter: ‘ruff’, ‘salmon’s tail’, ‘clack dish’ and the exquisite ‘quim’. If I were a rake in a London tavern in the late 1590s, I can well imagine fingering my ruff (as in puffy collar), and asking the bar wench for a clack dish of salmon’s tail with a side of fully dressed quim. Thats the sort of joke that would have had the 3000 Londoners that packed The Globe theatre every afternoon spitting out their cider with laughter, as Shakespeare happily fed an English craving for sexual allusions that, to this day, can simply never be quenched.

Thanks to Peter Ackroyd’s great act of literary love Shakespeare: The Biography, I now know these crucial literary statistics. But more importantly, I now also have in my brain a tableau of the wild, almost hallucinatory world of Elizabethan London, of the new artform that became a social obsession, the theatre, and the radical difference between the imaginary worlds the ordinary sixteenth century punter demanded to enter, and what we now demand to enter.

While the Elizabethan craving for innuendo is still a noble tradition carried on in Old Blighty and the former colonies today, what we look for in our performing arts and literary endeavours is in so many ways the opposite of what those 20 something garter and hose wearers flocked to see (did you know that the majority of sixteenth century Londoners were in their 20s? almost no-one lived beyond 40).

Elizabethan theatre goers wanted Artifice and Spectacle, speeches as massive and ornate as ballroom chandeliers, dazzling clothes (did you know Elizabethan theatre companies typically spent more than twice as much on costumes as they did on actors?), strutting play Kings and play Nobles, full lipped young boys cross-dressing, lots of narrative breaks for masques, finely turned ankles spinning jigs, sing-a-longs and lute strumming (final Shakespearean factoid: in 1600, one of the most popular Elizabethan comedic actors, William Kempe, performed a ‘nine day wonder’ by morris dancing all the way from London to Norwich. Is this starting to sound like the 1960s to you?)

The point being the common people had little or no interest in the common people and their common lives and their common thoughts and feelings, and the last thing they wanted to see strutting around the stage was someone who looked, dressed and spoke like them. Fast forward to the 21st century, and broadcast media (particularly in the USA) is being steadily strangled to death by ‘reality TV’ content, hop on a train and everyone’s head is bent over their mobile devices posting hourly updates of their ordinary lives and opinions for the rest of the developed world to take note of, and beside my computer now, there is a two foot pile of books I checked out of the Point Cook library a few weeks ago, all of them sincere, ingenious attempts by a huge variety of people to try and convey to me exactly what it’s like to be them.

I’m reflecting on the fact that in the late 1990s, early 2000s, we appear to have entered a Golden Age of Autobiography, in contrast to the Golden Age of Mellifluous Extemporisation, Poncing Around In Sparkly Doublets and Making Smutty Jokes a mere four hundred years ago.

And the reason I have checked out such a big pile of autobiographies and biographies is because I too, intend to add my own (fish-stockinged, morris dancing) weight to that pile – finally! – by spring. So I am doing my research.

How to represent yourself: the options

The two literary biographies in my pile are Peter Ackroyd’s epic biography of Shakespeare (equal in stature to his biographic homage to Blake) and Andrew Lycett’s no less epic documentation of Ian Fleming’s life (Fleming was the creator of James Bond).

What these two biographies have in common is obsessive mastery of the minutea of their subject’s lives and social spheres. But the evidence of intimacy that each writer has been able to draw on is vastly different. In narrating Shakespeare’s life, Ackroyd has inferred his subject’s life and character from a fascinating forensic study of hundreds of historical scraps and third party references – but there is not even a single letter that Shakespeare wrote that Ackroyd can draw on to shed light on his subject’s own self-representation of his mind and feelings. All that is left of Shakespeare’s interior life are what may or may not be displayed in his plays, a few contemporary reviews by (mostly) jealous fellow playwrites (he was commonly characterised as a plagiarist and womaniser), and one transcript where Will was called upon as a witness in a legal case- even there his words are interpreted and quilled by someone else, a court scribe.

Contrast that to Lycett’s access to the rich pastures of introspection (hundreds of letters, articles and cables) penned by mid-twentieth century playboy, aristocrat, sadist and wanna be spy Ian Fleming. (James Bond factoid: did you know that post-war British intelligence agencies really did develop spying tools like shoelaces that doubled as steel garrottes?). Thanks to Lycett, I now know the details of Fleming’s oxygen deprived upper class British life, exactly how this particular social butterfly, golfing addict and womaniser was genetically related to hundreds of other martini swilling club and media magnate species, celebrities and the wider British ruling class. And I know all the details of his war-time life, not as a spy, but as a significant organiser of navy intelligence operations. Lycett is fascinated but ambivalent about the object of his literary attentions. To the point that he does not even break a paragraph when Fleming finally dies, he simply notes it and carries on for a few more pages as if it there were some other story that we were following rather than Ian’s.

Ackroyd, however, pulls his narrative up to a stiff stop at Will’s death bed. He then wanders, with scarcely disguised sorrow, over visions of rival playwrite Ben Jonson’s London funeral procession – which included ” all of the nobility and gentry of the town” – then floats back to the Bard’s humble end where “only Shakespeare’s family and closest friends followed the bier to the grave” in Stratford Upon Avon.

The majority of my reference books, however, are autobiographies, mostly by writers or entertainers who have achieved some degree of success (I define ‘success’ as not needing a day job anymore).

In the case of William Shatner’s half-biography/ half ironic self help manual Shatner Rules, the original Captain Kirk informs us within the the first few pages that he has only ever been paid for being a performer/show pony, since the tender child acting age of eight. No part-time MacJobs. No waiting tables in LA or NYC. No slaving over spreadsheets in office cubicles. Ever. This guy is now eighty, and that statement alone was enough to hook me into the whole Shatner life saga.

Shatner’s book as it turns out is not so much a traditional biography as a series of extremely funny, sometimes poignant, always genuinely inspirational bunch of stories and reflections drawn from a showbiz life lived by someone who was not just five years ahead of his time but more like 40 years ahead of his time at any given moment. What is not to love* about someone who, in the 1960s gave a bewildered American television public an incantatory version of Mr Tamborine Man delivered as a junkie’s lament, rounded off by falling down on the studio stage, writhing on his back and screaming? And forty years later this same genius out-Jarvis’s Jarvis with the definitive version of Pulp’s Common People, with veteran new wave producer Joe Jackson, finding a poetry in the lyrics that even Shakespeare would have envied. Towards the end of his book, Shatner does share with us his dark fears about his advanced years and approaching mortality, as well as the environmental catastrophe slowly unfolding on this planet. But again with such charm and cool that it makes you wish you could purchase tickets to hang out with Shatner in the afterlife Starship, cruising around the final frontier of eternity.

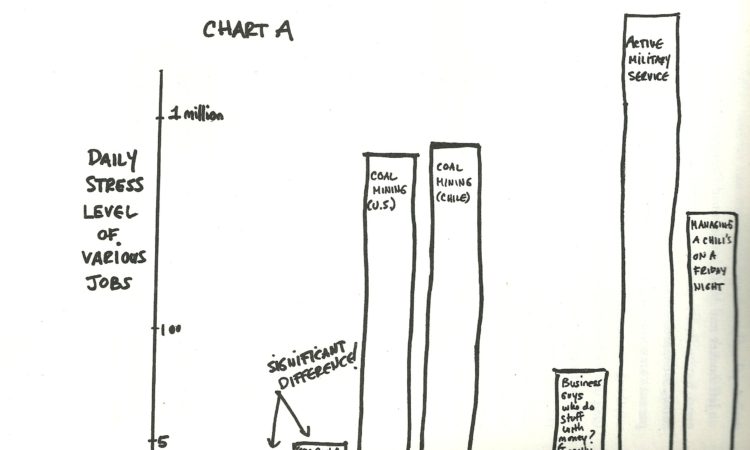

Tina Fey’s autobiography Bossypants, is also extremely funny and inspirational (any TV star who can produce the following diagram showing the relativities of stress in the entertainment industry versus working in a coal mine or destroying countries for a living has my vote):

While narrating her journey from high school dweeb to Chicago stand up comedy sensation to Sarah Palin look alike, Fey has a lot of important points to make about why women still struggle in showbiz to be considered ‘funny’. That this was even a question in any person’s brain was a revelation to me, first shared with me last year by local stand up wonder Fiona Scott-Norman who told me that she faces periodic musings by male critics as to whether a body containing a vagina (or ‘clack dish’, ‘salmon tail’ or ‘quim’) is able to make the common folk chuckle to quite the same degree as those born with a ‘waggle’.**

There is much to love* about Tina too. We need way more women like her at the producing helm to counter the entrenched LA cable exec attitudes of ‘is there anyone I want to f*ck in this show?’ as the sole assessment criteria of what kind of woman should be allowed to appear on screen.

My final*** autobiography was Jonathan Franzen’s The Discomfort Zone. I fell for* the Franzen schtick after reading his latest novel Freedom (anyone who can combine a Gen X pot-boiler page-turner with searing environmental messaging has my vote). Franzen’s life vignettes, including his scene by scene descriptions of a tortured ’70s adolescence spent at mid-Western Christian ‘Fellowship’ retreats alternated with elaborate high school pranks, are so brilliantly and seductively written that I was compelled to make the following late night notes on my beside notebook:

“Is this what readers have wanted all along, to peer into the unguarded hearts of each other? To see their own emotional turmoil represented far better than they could ever hope to utter?”

Well no. Only a few hundred years ago, the common people (ie folk of solid working class backgrounds such as myself) wanted nothing more than to see someone in a bear suit (or even better, an actual bear) running across a stage.

But now ‘authenticity’ is the cultural currency. Success is measured in terms of how well you can convince (first) yourself, (then) your readers that you are offering a bona-fide, original, non-photocopied version of your life and deepest feelings. But success is also measured in terms of how entertainingly you can split yourself in two and scribble down the other half. And only then will strangers reach out their hands and hold yours as you open the library catalogue of your mind and flick through card after card of the memories that make up the sum of your existence.

On that note

On that note, let me briefly tell you where my life is up to. In eight weeks time, my contract with the Victorian Department of Health will come to an end and I have no other day employment lined up. However, I aim to try and last between two to three months without working. I am going to take that time out to write my book about my life-changing adventures in the USA with the already best-selling title Jilted Brides in America.

As any patient followers of my sporadic blog would know, this is something that I have wanted/ needed to do for a long time. But I have been diverted by a series of ‘women’s health’ issues (there are penalties for owning a quim), and the pesky perennial need to focus on the ‘money problem’ to stay afloat.

Great things are happening on the music front though. The Dust Revival Band is half-way through our month of Sunday residencies at the Edinburgh Castle hotel in Brunswick, Melbourne, and we are having a lot of fun. This Sunday (17 June) we will be doing an interview and live to air performance on Australia’s largest independent radio station 3RRR, which you can also stream anywhere on this orb that is rounded with a sleep. After that we hope to record some new tracks and grow some beards.

So on that note, its good night from me, and its good night from her:-)

*Is there a term for the condition of ‘regularly falling in love with a writer’s charming literary persona’? Note to self: look that up in the latest DSM.

**’waggle’: penis. I just made that up. Pretty good isn’t it?

*** My pile actually includes a bunch of other autobiographies but they were so crappy I will not mention them.