As I remain in Australia slowly recovering from surgery, I have started a series of interviews with people who embody inspirational aspects of Australian cultural life. This is the second in the series, and it looks at independent, radical filmmaking as practiced by George Gittoes.

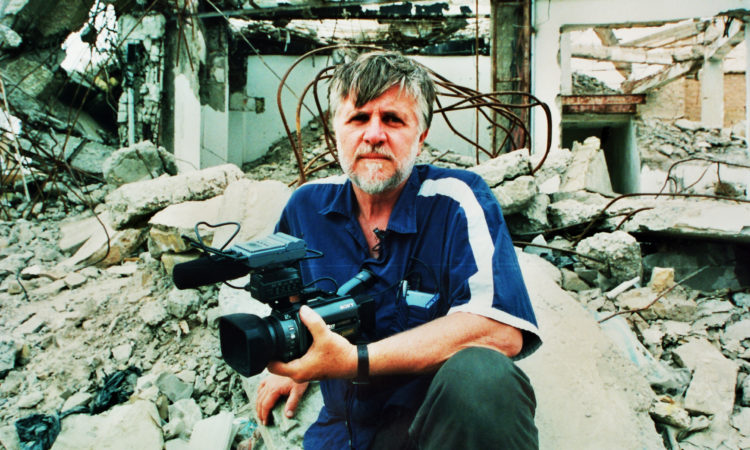

George Gittoes (b. Sydney, Australia 1949) has been working in the medium of film, for 30 years – he is also an exhibiting artist, photographer, and published writer.

Gittoes studied art in New York 1968-69, and returned to Sydney to form the infamous experimental artists co operative, the Yellow House, with Martin Sharp and Brett Whiteley 1970-71. He has represented Australia in Identities exhibition, Taiwan (1993), Inneseite, Documenta X (1997) and has been artist in residence at the Central Academy of Fine Arts, Beijing (1998) and a Fellow of The School of Humanities, Michigan University (2002).

In 1997 he was awarded an Order of Australia, AM for his services to the arts and international relations, and in 2008 he was awarded Doctor of Letters (honoris causa) by the University of NSW.

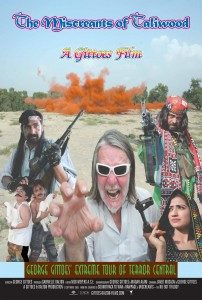

Gittoes has been working on themes of cultures in conflict since the 1980’s. He has worked in many regions including Afghanistan, China, Philippines, Russia, Middle East, Africa, Northern Ireland, and Nicaragua. Gittoes’ three most recent films (Soundtrack to War, Rampage and The Miscreants of Taliwood ) make up the trilogy ‘No Exit’ all made on the front line of the so-called War on Terror. As a film Director, he has been profiled in Berlin, Copenhagen, Stockholm, Raindance-London, Chicago, Vancouver, Montreal, Africa-Diaspora and MOMA Doc weeks, New York Film Festivals (2006-7).

Gittoes is currently working out of a studio in Berlin, but in mid- September 2010 he will be relocating to Houston, USA for an extended period. For more information on his prolific and provocative career, see his website.

Nicole: George, I know you as one of Australia’s most radical and innovative independent film-makers as well an award winning painter. War and conflict are major themes across all your work, what draws you to these themes?

George: The themes to do with war and its victims are my life’s work. To my knowledge I am the only artist in the world who has continually gone to the frontline of conflict to be a witness . I do it because I care about the people who are affected by the trauma of war and want to show them that I care. I also do it because I think it is important to create in the face of all that destruction. The anti war movement in the 60’s used to advocate love instead of war, I am from that generation and my way to demonstrate love opposed to war is to create in the midst of it .

N: Although you are Australian, you spend most of your time travelling the globe in search of subject matter, often documenting incredibly dangerous situations such as war zones in Iraq, Afghanistan, Rwanda and Bosnia. I’ve often wondered how you overcome sheer gut fear in those situations – does the adrenaline combined with the quest to highlight humanitarian plights do it? Or do you just have an unshakeable conviction that you’ll somehow come out unharmed?

G: I have seen so much death, often close by me, that I do not have any illusions about the possibility of being killed. It is worth risking your life for something worth dying for and for me it is art. I think more artists should do it and do not understand why it is only journalists who go to contribute about war when artists can communicate the experience in such a different way. I am not drawn to an adrenaline rush and find war very harsh and difficult to live through. Anyone who had been with me in these situations will testify that I am very calm and nothing like the stereotypical journalist as expressed in movies and books. My life out there is very insecure and uncomfortable.

As I prepare for another 5 months in Afghanistan my stomach churns and like always I worry that this next project could be my last. However, I am very happy to have the resolve to continue with this work despite all the concerns and anxieties because I can now look back on a huge body of work which is absolutely unique and full of meaning. War has made me appreciate life more. Rather than saying it has caused post traumatic stress and depression I would like to say it has had the opposite affect. I value every minute of my life and get incredible joy from the simplest of things which others would take for granted. Nearness to death makes you value every minute that you are alive. A patch of sunshine on some spring flowers.

N: You are a lauded veteran of the Australian arts and film scene, but you have also spent a lot of time in America, starting way back in the ’60s when I believe you first went to NYC to work with Andy Warhol. In relation to independent, political film-making, what differences do you notice between the Australian and American scenes and has this changed over the years?

G: I can not talk about either the Australian or American scenes as I have never belonged to any scene or taken notice of the circumstances of those who do. Usually I have to patch the funding together in an inspired way that does not follow any general film financing guideline and it is the same with my art. It has been a difficult struggle and at 60 I feel as insecure as ever.

America is starting to open up for me in a way Australia never has. The difference is that the gatekeepers in the Australian art world are extremely conservative and frightened to make decisions about art like mine. I have always been made to feel like a maverick outsider in Australia and my paintings still have not been collected by the Art Gallery of New South Wales, the National Gallery in Canberra or the Museum of Contemporary Art (Sydney). The curators in these institutions are frightened to include or show it. Critics such as John McDonald attack my work at every opportunity and I have never been considered for a Sydney Biennale or the Asia Pacific one in Brisbane. It is difficult not to feel excluded and hurt by this. The US on the other hand is enormously supportive. All three of the recent films have been shown at MoMA (NYC) and I have major Museum shows, such as the one at Houston Station Museum of Contemporary Art coming up . I also have a huge support base among critics, curators and festival directors in the US who take my work very seriously. A quick google search will verify this.

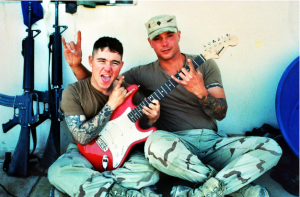

N: As a musician, I was simultaneously fascinated and horrified by your portrayal of the role of pop music in motivating troops in your unforgettable documentary Soundtrack To War, shot in Iraq and also referenced in Michael Moore’s Fahrenheit 9-11. What inspired you to make that film?

G: I love popular culture and cannot live without music as a background to my life. Soundtrack to War came about when I realized most young people in America who were the age of the soldiers being sent to Iraq do not watch the news or documentaries but do watch MTV and VH1 . I decided to do a portrait of this MTV generation going to war and have it seen by them on MTV’s VH1. I was successful in doing this. It mainly shows the role of popular culture in war in both positive and negative ways.

N: In Rampage, You take some of those soldiers in Soundtrack to War and follow them back to their homes in Brown Sub (Brownsville), a ghetto in Miami, where you vividly make the point that these people grew up in a war zone. Its a gripping portrayal of the desperate situation of black youth gangster sub-culture, and the role of rap as offering both a mirror and a kind of poetic escape. Its one thing, though, to highlight American foreign policy failings overseas – its quite another for an Australian to dig around American tragedies on their home turf. How was the film received in the US?

G: American audiences get a lot of the references better than Australians who are less familiar with this scene. Rampage is a hard pill for Americans to swallow just as a film on the stolen generation or petrol sniffing among aboriginal youth would be for Australians. I considered Brownsub another war zone and that horrified Americans who only want to see war and poverty like this in other countries.

It is still a powerful film to show in the US and does not date, especially with Obama in the Whitehouse. I have recently been showing it at various University Campuses throughout the US and getting even stronger and more appreciative reactions than when it was first shown there and I think it is because the recession has made Americans more aware of the poverty and the growing hopelessness within their borders. When the film first came out Americans knew the poverty was there but did not want to admit to it and certainly did not want a foreigner putting it up to their faces. I remember when Penny Tweedie, the English photo journalist, did a slide show to music for the first Sydney Festival, called The Fat Australians, it contrasted the wealth of much of white Australian society with the poverty and desperate look of aboriginal settlements and camps. White Australia did not like it but liked it less because it was an outsider who showed it to them.

N: It looks like the US is embracing your latest film The Miscreants of Taliwood. I haven’t seen it, but I understand the title derives from the Taliban’s list of ‘miscreants’ which includes singers, dancers and store owners who sell music videos of any kind. You shot most of the film in Pakistan’s Taliban controlled tribal belt, in the North West Frontier Province. I see the film has caught the attention of CNN, and was recently on exhibition at NY’s MOMA. Can you tell me about this film and why you made it?

G: I made Miscreants as a way of defending the artists of the Tribal Belt of Pakistan’s North West Frontier who have been prevented from making films, singing, dancing, painting and creating poetry by the Taliban. I have a level of access to this region impossible for other foreigners. This is because of the many years I have worked with NGO’s in the region to assist landmine victims and promote mine awareness. This is a time when bridges of understanding need to be built between Islamic cultures like this and the rest of the world. I felt I had an obligation to be a bridge builder and give insights into this poorly understood region. I have a real love of Pashtun culture and have even contemplated buying a studio in Peshawar and making it my main base in the world. I have studied and enjoyed Islamic art and literature since I was at Kingsgrove North Highschool where I chose to specialise in Islamic art as an elective. I also feel closer to sufism than any other system of philosophical thought and Peshawar is a centre for Sufi scholars .

N: No-one working in independent film finds it easy to find finance, and in Australia $2m is considered to be a pretty good sized budget. Can you find the backing you need in Australia for your radical films, or do you need to go overseas?

G: I tend to get a portion of my funding from organisations like Screen Australia although they were not involved with Miscreants except for a small research loan. Most of my funding is scrounged together from painting sales and returns from the previous films . I have never gained any funding from overseas sources.

N: Finally George, have you ever met George Romero ? I recently moved to Pittsburgh which is George’s old college town. He shot his most famous films Night of the Living Dead (1968) and Dawn of the Dead (1978) there, and Tom Savini, the legendary make-up artist and ex Vietnam war vet, used to work out at my local gym! Pittsburgh is as beautiful and hilly as San Francisco, except most of the best views are dominated by graveyards: it is rightly considered the zombie capital of the world. Although Romero uses horror as his genre, he is, as you know, an extremely astute and critical observer of Western consumerism and many of his films are quite subversive. Have you ever considered doing a zombie movie? (Please come to Pittsburgh if you have!)

G: It is amazing you ask that. I wrote a zombie story a few days ago and am working on a Living Dead painting at this very moment. I have considered doing a Vampire and Werewolf movie in Afghanistan with my Pashtun drama crew of actors and filmmakers. This would be a background to a documentary.

I would really like to meet George Romero and would be very happy if you could put us together. I have not seen either of those movies but will have to do it soon. Horror movies give me bad dreams in a way that the worst experiences of the atrocities of war never do. I really am too sensitive to watch horror movies as they awaken a fear deep in the soul and I believe there are much worse things to fear than physical death.

I will attach my recent Inferno Texts for you to read. I am exhibiting these texts with my recent paintings done in Berlin and visitors to the exhibition will feel they are walking through a graphic novel or rather an illustrated Tibetan Book of the Dead .

N: I don’t know George Romero personally, but am currently working on a little mini-doc about Pittsburgh zombie culture so hope to get in touch with him soon – will attempt a virtual introduction when I do! Thanks so much George, good luck with your forthcoming exhibitions.

G. Thanks. Might see you back in the States.